The warning bells have been ringing for at least two decades: The legal profession as we’ve known it is doomed, and lawyers must adapt—or face extinction. For the most part, these dire predictions have been ignored, even as globalization and technology have revolutionized markets, affecting everything from airline travel to taxicabs. Yes, law firms have been outsourcing legal research to India, and electronic discovery is taking over some basic tasks. But lawyers have tended to see themselves as immune: a guild of highly educated advisers whose wisdom, savvy and deep understanding of a complex series of laws are irreplaceable.

Then a computer named Watson beat a human on “Jeopardy!” Now all bets are off.

Watson’s victory showed that artificial intelligence can master what was considered a uniquely human realm: using judgment to select best options after sorting through huge amounts of complex information communicated in real language. Cancer doctors from the nation’s top research institutions were among the first to recognize the broad implications. Today, they are working with the IBM Watson project to sort through massive amounts of data to try to find new ways to diagnose and cure the disease. If a computer can displace doctors—or at least, significant aspects of what doctors do—who’s next?

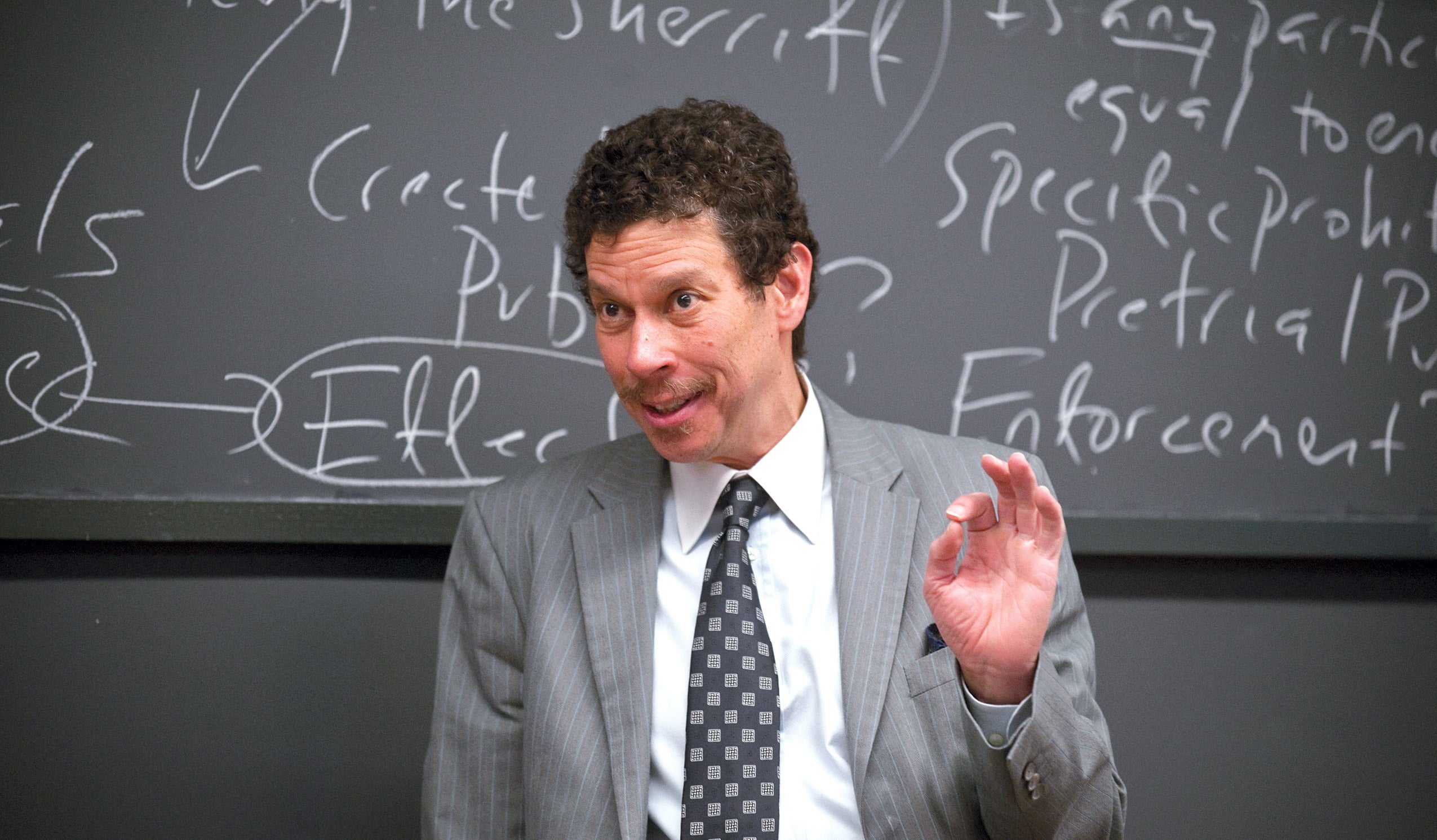

In fact, lawyers may be far more susceptible than physicians, says Harvard Law Professor David B. Wilkins ’80, vice dean for global initiatives on the legal profession. As a rules-based system, law is similar to chess, he notes, in which Watson’s predecessor, Deep Blue, prevailed 14 years earlier, beating the world chess champion.

“The Watson people say, ‘We won’t replace doctors or lawyers; we’ll just help them be more effective,’” Wilkins laughs, adding, “But of course, they will replace some doctors and lawyers.” The question, he says, is which kinds of lawyers, and how big a share of the legal market?

Because of technology, globalization and other major market pressures, “law is ripe for disruption,” says Wilkins, faculty director of the HLS Center on the Legal Profession, which is a leader in research and analysis in this area.

Disruptive innovation, a term coined by Clayton Christensen, a professor at Harvard Business School, occurs when existing patterns of work and organization are radically transformed in a relatively short period of time, when new competitors arrive to offer low-cost alternatives at the bottom end of the market. The incumbents ignore these upstarts—until the disruptors become the norm and the old guard adapts or is replaced. Personal computers replacing mainframes, cellphones replacing landlines, retail medical clinics replacing traditional doctors’ offices, and Uber replacing taxis are important examples, Wilkins says. The legal market—which has maintained some of the highest profit margins for professional service businesses—faces the same challenge. Legal information is being digitized, and low-level tasks are being outsourced. Now the inspiration aspect of legal work—the solving of complex problems—could soon be facing competition from sophisticated computers. Meanwhile, consumers are turning eagerly to low-priced alternatives to traditional lawyering, such as online divorces and wills, and new online matchmaking services through which lawyers can compete for clients—like Uber, but for law.

Avvo, a tech-savvy method making it easier and cheaper for people to get legal advice, was founded by Mark Britton, the first general counsel for Expedia, which revolutionized travel planning. Shake, a new technology that provides consumers with online contracts, legal advice and other legal services for free—or at very low prices—has this mission statement: The “legal market is huge, inefficient, underserved by technology, and begging for change.”

High-end lawyering won’t be immune, since clients there, too, are looking for alternatives.

Indeed, Legal OnRamp, a virtual information-sharing platform for lawyers launched six years ago, is working with the IBM Watson project and major banks to figure out how Watson can help banks analyze tens of thousands of derivative contracts in order to respond to the “too complex to manage” challenge, says Paul Lippe ’84, Legal OnRamp’s CEO. That collaboration sprang from a summit of representatives from banks and major law firms in July, which itself grew out of a 2014 HLS conference, “Disruptive Innovation in the Market for Legal Services,” sponsored by the Center on the Legal Profession, Lippe says. At the same time, a leading New York law firm is working with OnRamp to “Watson-ify” some of its large M&A client engagements. “No one is looking to ‘disrupt’ per se,” Lippe says, “just find ways to manage work better in a complex world.”

The relative resistance to innovative technology is seen as cultural or structural, “but it actually is a finite phenomenon that arises from the market dynamics of the last 30 or 40 years,” says Lippe. As those dynamics shift dramatically, so does the imperative to innovate.

Indeed, since the financial crisis of 2008, all clients—especially general counsel at major companies—have had more market power than ever, “and they aren’t likely to give it back,” says Scott Westfahl ’88, HLS professor of practice and faculty director of Executive Education.

“The leverage is now all with clients,” agrees Romeen Sheth ’15, who this year won an international competition in legal innovation by designing a cloud-based system for managing M&A work.

In other words, lawyers not only have the capacity to adapt—they have to, at all levels of the profession. While these legal disruptors currently are focusing on the easiest targets, such as legal research, “eventually they will go on to other things,” says Wilkins. The implications are huge not just for Big Law but for lawyers across the spectrum, including the 80 percent in the U.S., in small firms or solo practice, who will have to figure out new ways to offer services at lower costs. Some of the biggest winners may be the low- and middle-income consumers who will finally have access to affordable legal services through these new alternatives, he says.

These changes also mean a shift in the way law is taught. “We need to teach students how to unbundle legal problems and collaborate across organizational boundaries with other providers, which is the biggest challenge,” Wilkins says. “We have to work across divides, including with the disruptors themselves.”

Eyes on the Profession

No one should be surprised by the rise of new forms of competition to traditional legal services, says Wilkins, who has been studying the legal profession for 30 years. Yet many lawyers, he says—including at sophisticated law firms—remain quite unaware, or unconvinced. “I find when I talk about this, particularly to people who are not quite in the middle of it anymore, they are stunned,” he adds.

The HLS Center on the Legal Profession is exploring better ways to evaluate the quality of lawyering.

The Center on the Legal Profession is focusing significant resources on disruptive innovation in the legal market, with data-driven research; publications including its digital magazine, The Practice; executive education; and the convening of top thought leaders from around the world. Last year’s conference on disruption included Christensen and others leaders, such as Mike Rhodin, senior vice president of the IBM Watson project.

Wilkins expects disruption at all levels of the legal world. But unlike some others, “I don’t think we’ll see the death of Big Law because there will always be a space for sophisticated legal services,” he says. However, “the question is how big that space will be and how many will be in it. For high-priced, high-profit-margin work, how much of that could be done by other providers?”

There is plenty of opportunity for lawyers who are willing to adapt: Megafirm Morgan Lewis, for example, has developed its own electronic discovery department so clients won’t go elsewhere for that aspect of services. Lawyers willing to make these kinds of innovations themselves have a natural advantage because the legal disruptors haven’t yet really figured out the legal market, Wilkins says. “They’re a bunch of hammers looking for nails. They equate everything we say about the distinctiveness of practicing law as protectionism, but I don’t think that’s true. Lawyers are not exactly like taxicabs, which can be replaced by Uber”—although, he warns, “they’re a lot more like cabs than lawyers want to think.”

Without a good way to evaluate legal work, consumers may see no difference between filling out an online contract and getting the guidance of an experienced lawyer. “The disruptors are mostly trying to measure quality in the same way Uber does, which is through customer satisfaction. That’s not irrelevant but it’s a very crude measure of quality and might work less well in law, particularly where consumers are less sophisticated about the quality” of what they’re getting, Wilkins says. The center is working to develop better ways to evaluate the quality of lawyering.

“None of this means that law firms are going to disappear, I don’t think,” says Wilkins. “But I do believe there’s a significant amount of change coming and we shouldn’t be surprised—because we’ll just be seeing in law the kind of change we’ve been seeing in the rest of the economy.”

Innovation Training

In the new economy, Westfahl believes, collaboration is among the most important skills. Last spring he launched a new team-based course at HLS, Innovation in Legal Education and Practice.

Drawing from other disciplines, including neuroscience and psychology, Westfahl modeled the course on the work of Michele DeStefano ’02, a professor at the University of Miami School of Law, who is a visiting professor at HLS this academic year. The course teaches students how to design and maintain effective teams, requiring them to work to identify challenges in the legal world and come up with solutions. Among team proposals were a better mentoring program for new HLS students, and a means to encourage mindfulness meditation training at law firms in order to lower stress and increase error-free productivity. Class participants say the collaborative approach has been a liberating experience.

“Students in law school are taught to be apex predators, alone and armed to the teeth against everyone else. But these days, that is [neither] a feasible way to build a practice nor how the law works,” says Caitlin Hewes ’15, who was part of a team that designed ways to make the 3L year more efficient and useful.

With 80 percent of students entering HLS with at least a year of work experience after college in a wide variety of settings, “we need to leverage that experience,” says Westfahl. “It’s a huge gift to the law school to have all these people here together.”

“The skills involved in being able to come up with an innovative proposal, to make a compelling presentation as a team in front of real-world, critical judges—that’s what law students will be called upon to do later in life, and the majority of them will need those skills,” says Westfahl. “We haven’t traditionally helped law students understand how to work effectively in teams; [this is] unlike business schools, where teamwork and building networks are seen as a central part of the educational process.”

Law schools could make real strides by adding a business-case-type problem into torts, civil procedure, and other classes, he says, “so we could build skills without sacrificing traditional educational and critical legal thinking, which we do well and shouldn’t give up.” He and Wilkins are two of the seven instructors for the HLS Problem Solving Workshop, which uses such methods and is required of all J.D. students.

Westfahl also draws on his experience heading up Executive Education at HLS, where managing partners at major law firms and other legal leaders exchange ideas and gain cutting-edge exposure to the world of disruption and innovation. “How do you rally your team? How do you work with others in the business to get to the right answer?” asks Fred Headon, assistant general counsel for labour and employment law at Air Canada, and chair of the Canadian Bar Association Legal Futures Initiative, who recently took the HLS executive education course. “That’s a skill set that’s crucial to successfully practicing but is something that doesn’t really show up on the curriculum of most law schools.”

As Westfahl notes, innovation is not something many lawyers are trained to foster, however much they believe they are: “A managing partner will call in the professional development people and say, ‘We really need to do something innovative on how we recruit. What’s everyone else doing?’”

Disruptive innovation is not limited to Big Law and servicing corporate clients, Westfahl emphasizes; he, like Wilkins, sees enormous potential for solving a broad range of law-related problems, including access to justice for low-income people.

Some HLS clinics are already exploring that potential. The HLS Cyberlaw Clinic, for example, has been assisting the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court as it seeks to leverage new technologies to help people, including pro se litigants, navigate the legal system.

“I’m excited,” says Westfahl. “The evidence is right in front of us, that if we help students and lawyers to work together more collaboratively, to understand how to work in teams and how to drive innovation together, our graduates and the lawyers who come to our programs will have so much more impact on the world.”

Thinking Outside the Walls

In the fall of 2010, frustrated by how slowly the legal world was responding to the fast-paced changes swirling around it, Michele DeStefano ’02 launched an innovation space for law students and lawyers.

“I felt that the world was changing but the law market, legal educators and lawyers were not changing to meet the 21st-century marketplace,” she says.

Law students have been traditionally been taught to be “apex predators, alone and armed to the teeth.”

Her creation, LawWithoutWalls, a kind of “American Idol” meets “Shark Tank,” has grown from 23 students each year to 100, from an initial group of six law schools (HLS among them) to 30 law and business schools. It now comprises 750 “change agents”—academics, lawyers, multinational business professionals, venture capitalists and others—in a global “collaboratory” dedicated to innovating the future of legal education and practice, DeStefano says.

“There’s nothing else like it, and that’s what makes LawWithoutWalls so rewarding—that I can be a catalyst for change,” she says. “I help students find their passion that was either buried or that they didn’t think they could apply to law.” Students who apply are selected because they can add value to the collaboratory and can benefit from it—their law school grades aren’t even considered, she emphasizes.

Combination hackathon, conference, webinar, and professional network, LawWithoutWalls convenes students from around the world and places them in teams with a broad base of mentors: lawyers, academics, businesspeople. It charges them with identifying a problem in legal education or practice and gives them four months to create a business plan for a startup that would solve that problem. It kicks off with interactive exercises to foster idea generation and teamwork; then, using the latest technologies, teams e-meet every week. Finally, they present their proposals before a panel of multidisciplinary judges including venture capitalists.

LawWithoutWalls teaches skills not emphasized in traditional law classes or executive education courses, including cultural competency, teamwork, presentation skills, communication, project management and leadership, says DeStefano, who worked for eight years in the business world before attending HLS and helped the school launch its executive education program. It has also become a global multidisciplinary network that breaks down barriers between lawyers and clients, law and business, and professors and students. Its supporters and participants include major international law firms such as London-based Eversheds, as well as American Express and the Ethics Resource Center.

Among its student proposals in the startup stage is Advocat, a multilingual computer interface that helps immigrant children in the federal detention system work with their advocates. A national leader in advocacy for these children—there are 70,000 immigrant child detainees in the U.S. today—is looking to pilot Advocat across the U.S. Another project, the website and app ProBono123, connects law students and lawyers with pro bono opportunities and tracks and verifies their hours

“We have to work across divides, including with the disruptors themselves.”

In September, LawWithoutWalls won the Faculty Innovative Curriculum Award from the International Association of Law Schools.

“I set out to transform the way law and business professionals partner to solve problems,” says DeStefano. That transformation starts, she believes, with helping today’s law students think differently about innovation and creativity in the legal world.

Student as Innovator

“If HLS produces one innovative company that changes the legal industry, that’s blockbuster success. I think the possibility of that happening is very, very high.”

So says Romeen Sheth ’15, who someday may very well do just that. In April, as a 3L, Sheth won the international LawWithoutWalls competition. His team created CORE—a product that helps law firms and in-house lawyers manage their use of legal process outsourcing and better analyze its value—and they won $25,000 in seed capital to develop it further.

CORE isn’t Sheth’s first legal innovation. During his 1L summer at a law firm in Atlanta, he was perplexed at the incredibly outdated, inefficient way firms manage M&A work. “You have 150 shareholders signing 10 documents each, which they’re sent in an email, and I’m keeping them all tracked and collated, marking them off in a Word document—this is a terrible, terrible process! Lawyers hate it, and we’re not billing for it,” he recalls. Calling upon his experience in other industries, including with hedge funds, which he says are miles ahead of law technologically, Sheth devised a cloud-based project-management system to streamline the process and help stakeholders communicate better, a system he developed at the Venture Incubation Program at the Harvard Innovation Lab.

“This has nothing to do with lawyers wanting to change—it has to do with them wanting to have a job,” says Sheth, who is now the business development lead at Ravel Law, a Silicon Valley startup that has raised $9.2 million to improve the analytics behind legal research. “In this economic environment, they have to evolve.”

Yet law is a conservative profession, and lawyers remain averse to new ideas. In an article he wrote for The Practice, Sheth noted that legal startups aren’t thriving: Investment in them declined sharply last year after attracting $150 million in 2013. Among the barriers was that lawyers tend to want an idea to be fully developed before they’ll invest in it, which precludes the iterative development that leads to startup success. And the billable hour incentivizes inefficiency, so technology that reduces it eats into the bottom line.

Despite the obstacles, “I think in the next five to 10 years, the legal industry is going to dramatically change,” says Sheth. “To me, it’s a no-brainer—this industry will be completely turned on its head.”