A typical Harvard Law School student has limited free time. It might be filled with journal work, or student practice organizations, or intramural sports. For large portions of their 1L and 2L years, (2015-2016), HLS students Crispin Smith, Nick Gersh, and Ahsan Sayed spent their free moments exploring the successes and challenges facing religious and ethnic minorities in Iraqi Kurdistan on behalf of the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom.

They worked with a team of nearly a dozen researchers, including incoming HLS 1L Vartan Shadarevian ’20, to craft a groundbreaking 75-page qualitative and quantitative analysis of a region that is regarded as a refuge for religious minorities in the Middle East. The report was published in June and primarily co-authored by Smith and Shadarevian.

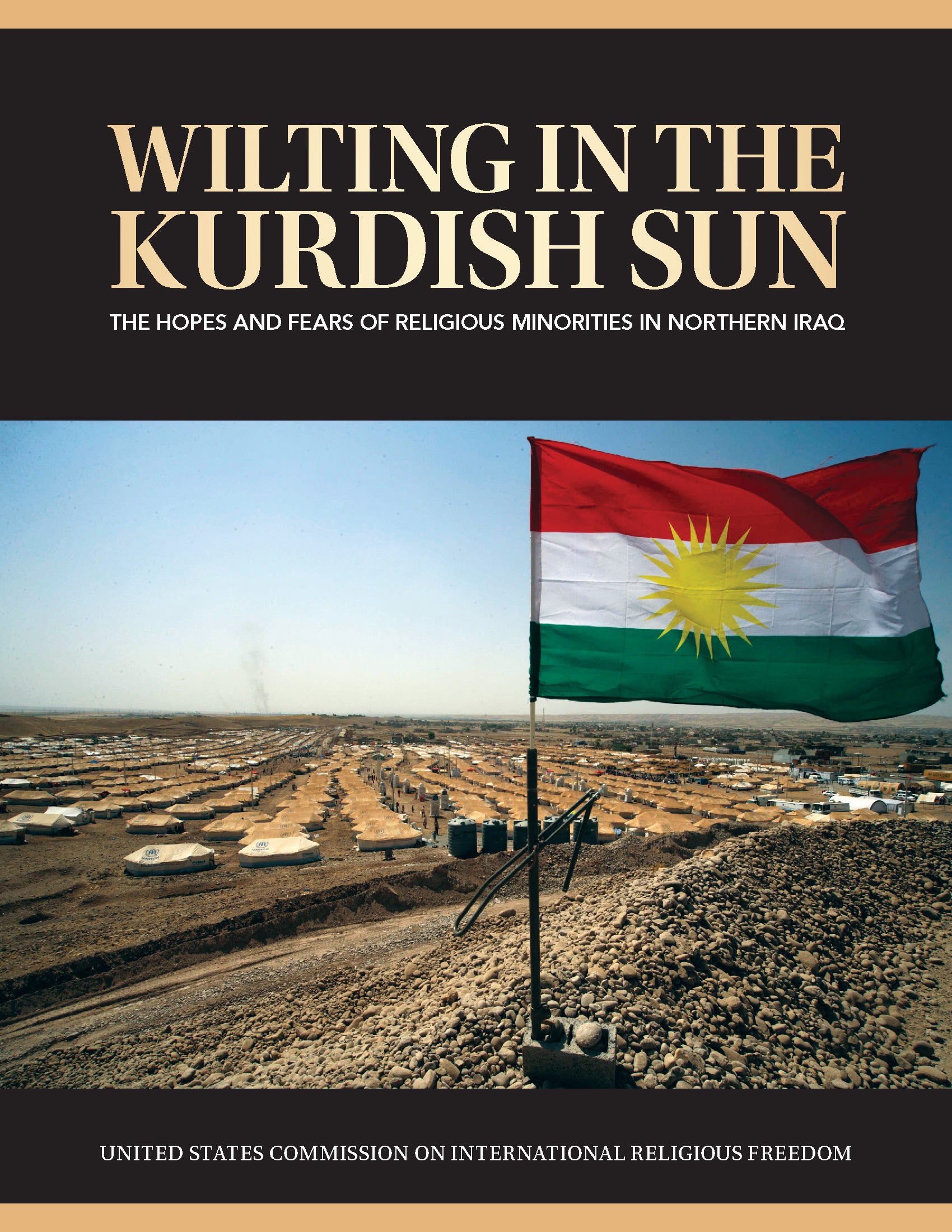

Titled “Wilting in the Kurdish Sun: The Hopes and Fears of Religious Minorities in Northern Iraq,” the report highlights the successes and unique challenges of securing freedom and tolerance for religious and ethnic minorities in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. This region is home to more than a dozen religious and ethnoreligious groups, and even more subgroups, and is widely credited for its relative tolerance of religious minorities, many of whom have fled there to escape the violence of the Islamic State. Nevertheless, the team’s research found that examples of discrimination and violence targeting minorities persist, but are often overshadowed by a general lack of stability and security, or not prioritized because of Kurditans’s relative success compared to other parts of the Middle East.

“Just because they’re doing better than Iraq and fighting ISIS doesn’t mean there are not really serious issues in the region,” Smith said. “The trends we’re seeing are trends away from rule of law for certain minorities, and towards majoritarian rule at the expense of the rights of groups who have already suffered pretty terribly in the region.”

The team was led by Shadarevian, who grew up in Syria and is a political economist and former researcher with the University of British Columbia’s Liu Institute for Global Issues. Smith’s background includes a degree in Assyriology and Arabic and service in the British Army (he is currently on leave from HLS, on active military service). He has also conducted research concerning Syria, Iraq, and other foreign policy issues for the U.K. House of Lords and several NGOs. After being approached by a former colleague who recommended that he bid for a contract to draft the report for USCIRF, Smith invited Shadarevian, with whom he had studied at Oxford University, to join him. Shadarevian ran day-to-day operations from his home in Vancouver, while Smith spent the summer after his 1L year leading fieldwork in Iraq.

Smith’s on-the-ground team spoke to nearly 100 individuals on the record and hundreds off the record, including Arabs, Kurds, Yazidi, members of multiple Christian denominations, Kaka’i, Shabak, Armenians, Turkmen, and Zoroastrians. In addition to the qualitative breadth of the report, Shadarevian also managed a team of researchers who used econometric techniques to build ethnoreligious maps of the area and to analyze its various economies.

Although the project was not formally affiliated with Harvard, nearly one third of the contributing researchers were connected to the law school in some way. Gersh, who had previously worked on issues involving Syrian Christians for the U.S. government, joined the team after mentioning his work to a section mate, who put him in touch with his dormitory neighbor, Smith. Gersh took on a section of the report concerning how the legal system in Iraqi Kurdistan allows abuses against minorities to occur. Likewise, Sayed and Smith were section mates, and the two quickly bonded over their common academic and political interests. Sayed took on a small role providing background research on Sunni Islam in Northern Iraq and Kurdistan.

The team also benefitted from the insights of Harvard faculty, including HLS professors Jack Goldsmith, Noah Feldman, and Naz Modirzadeh ’02.

“Because Harvard attracts people with interesting backgrounds and experiences, we were able ultimately to connect and start off on this adventure together,” Gersh said. “I cannot imagine a connection like this occurring at any law school outside of Harvard.”

The team’s work now extends beyond the confines of the paper. The group has formally organized as the Aleph Policy Initiative, which will continue to provide policy research for government and non-government organizations. At the end of last year, Smith and Shadarevian presented their findings to a Canadian parliamentary group, and in July signed a contract with the Canadian Parliament to pursue work similar to the USCIRF report. The researchers have also been contacted by aid organizations who work on behalf of refugees to provide evidence that individuals belonging to ethnoreligious minority groups experience violence and persecution. In the United States, a bill currently pending in Congress incorporates passages of the report in recommending emergency relief for victims of genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes in Iraq and Syria.

Smith, Shadarevian, Gersh, and Sayed are unsure how much of their future work will focus on the challenges faced by religious minorities in Kurdistan. They are certain, however, that the world will continue to watch this region as a beacon—or a lesson—for the Middle East.

“Kurdistan is the last chance to show that you can have a pluralistic, not-very-focused-on-religion country in the Middle East and have it be successful,” Gersh said. “It’s important to hold the Kurds responsible so . . . you can have an actual example that, in the future, other countries can look to. Kurdistan is the best hope for planting that seed right now.”