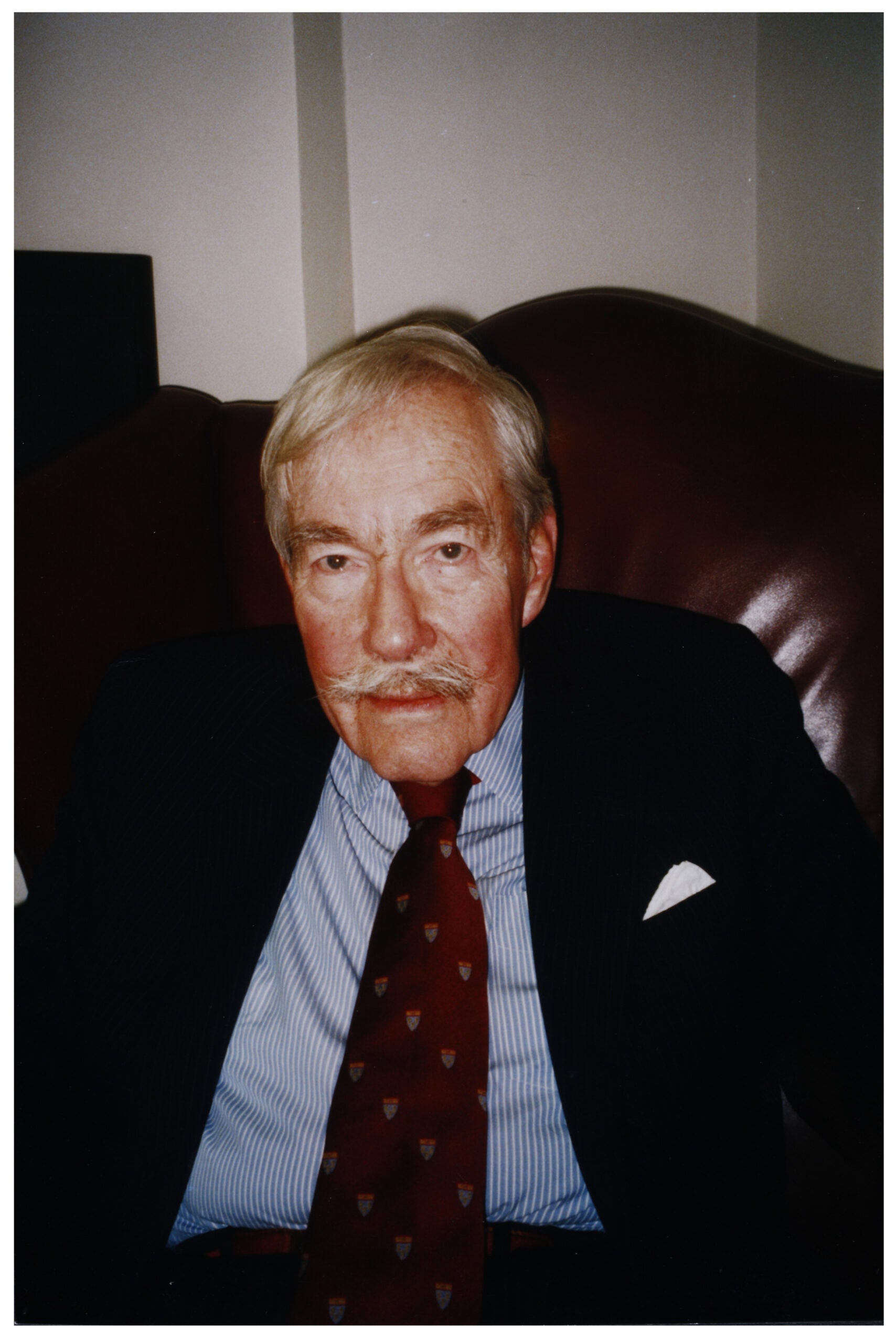

J. Sinclair Armstrong ’41 credits the faculty at the School in preparing him for his life and career. He has also taught himself to conquer new fields of expertise, and to face new challenges at the top levels of government and business.

His background and abilities have transformed a novice in the securities law field into the head of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission; a Naval Reserve assignment into a post responsible for the entire budget of the Navy and Marine Corps; and an interest in historic preservation into a decade-long, winning battle to save a New York City landmark. Today, he builds on his successes to support the School and causes he holds dear.

After graduating from HLS, Armstrong became an associate at the Chicago law firm Isham, Lincoln & Beale, where he specialized in corporate securities, despite no earlier coursework in the area. After he made partner and served on the Corporation Law Commission of the Chicago Bar Association, Armstrong’s name was submitted to President Eisenhower for a place on the SEC. He began in 1953 and was designated chairman from 1955 to 1957, concentrating on policing against stock market abuses and recommending the now standard practice of company reports and informative proxy material for investors.

After his SEC appointment, he served as assistant secretary of the Navy, as the U.S military was competing with the Soviet Union in the Cold War. In order to learn about current weapon systems and their costs, he traveled to training stations, shipyards, and aircraft factories throughout the United States, including Hawaii and Guam, and to Japan.

“The major challenge was how to convert the World War II Navy to the new technology to keep the Navy militarily ahead, and within President Eisenhower’s balanced budget objectives. We did it,” Armstrong said. “I gained a far greater appreciation of military life, the devotion of the people who worked in military service, and the need for them to be properly housed, paid, and respected, and their dependents cared for.”

He then became executive vice president of the United States Trust Company of New York, at which, he said, “I started a corporate trust department and made the company a lot of money.” Next, he became partner, and later counsel, to Whitman, Breed, Abbott & Morgan, where he continued in securities and banking but also worked in historic preservation law, which became a passionate cause.

As a member of St. Bartholomew’s Episcopal Church, at Park Avenue and 50th Street, Armstrong led the fight against the church’s efforts in the early 1980s to build a 60-story office building cantilevered over the church. The church contended that the site would supply needed cash; Armstrong and other parishioners countered that the church had adequate resources and that a skyscraper would besmirch the historic landmark edifice. Armstrong emerged victorious in 1991 when the Supreme Court let stand lower court rulings that the city was justified in maintaining St. Bartholomew’s landmark status. Today, Armstrong notes that the church is “thriving” even without the hoped-for revenue from the proposed office building.

Currently, Armstrong is devoting his financial acumen to The Reed Foundation, where he serves as a director, executive secretary, and treasurer. The New York City-based charitable foundation allocates its income for programs in human rights, medical research, and archeological and cultural activities in South and Central America and the Caribbean.

He also serves as an independent director of The Bramwell Funds, open end equity mutual funds.

He and his wife, Charlotte ’53, former president of the HLSA and the university’s Board of Overseers, retain close ties with the School. In recognition of his career, the Law School designated a professorship in his name in International, Foreign and Comparative Law, a chair held by Professor Anne-Marie Slaughter ’85. “We are extremely proud to have her as the first professor in the chair,” he said.

Recently he penned a reminiscence of his time at the School, mentioning classmates who had rendered distinguished public service, and paying tribute to the “world-class faculty who taught us, sometimes roughly, sometimes gently, but always with their students’ interests at heart.”