Former U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Samantha Power ’99 expressed both skepticism and hope for the current state of international affairs during a panel discussion at Harvard Law School Monday.

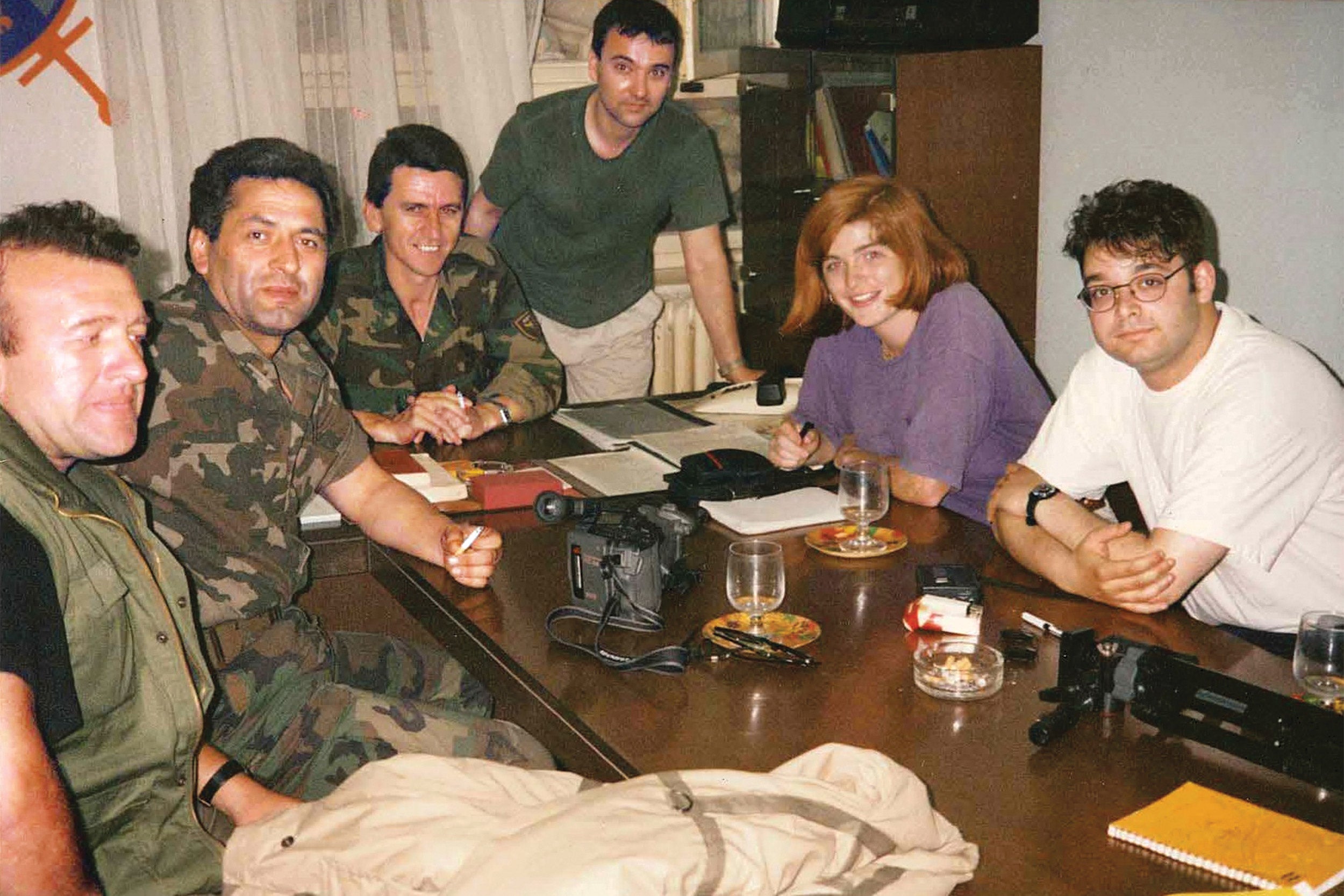

Power, whose new memoir, “The Education of an Idealist,” documents her journey from “immigrant to war correspondent to presidential Cabinet official,” argued that the legitimacy of institutions like the United Nations is largely predicated on that of its members states. When those nations’ leaders undermine that legitimacy, or squabble among themselves, the effectiveness of international institutions also suffers.

“Certainly, the division and then the attacks on democratic institutions by our current leadership … really impact the United States’ ability to influence human rights around the world within the U.N.,” she said. These divisive attacks also impact the United States’ ability to build coalitions to hold governments accountable for war crimes or other abuses, or to lead on issues like LGBTQ rights, she added.

Power, who is currently teaching at Harvard as the William D. Zabel ’61 Professor of Practice in Human Rights at Harvard Law School, and the Anna Lindh Professor of the Practice of Global Leadership and Public Policy at Harvard Kennedy School, previously served as the 28th U.S. Permanent Representative to the United Nations from 2013 to 2017, and was a member of the cabinet of President Barack Obama ’91.

Citing the presence on the U.N. Security Council of China, Russia and the United States, led respectively by Presidents Xi Jinping, Vladimir Putin and Donald Trump, Power argued that their conflicting agendas and the resulting rivalries have led to a level of geopolitical gridlock. “Having one of them in charge would be very problematic in my view, but also to have the three of them, with all of the … collateral damage from the bilateral tensions between them, really hobbles the international system as a whole, at just the time, as you know, that people need to do more,” she said.

At the same time, she said, despite what she termed “the human rights recession,” we are “still at or near an all-time high for democracy around the world.” From Hong Kong to Turkey to Egypt, Power cited examples of “the inexhaustible aspiration people have to hold their leaders accountable and to be treated better.”

The event, which was co-sponsored by the Harvard Law School Library and Harvard Law School’s International Legal Studies, also featured a panel discussion with Harvard Law School Professor William P. Alford ’77; Harvard Professor of Government and former Dean of the Harvard Kennedy School Graham Allison, and Harvard Kennedy School Professor of Practice Wendy Sherman, a former U.S. ambassador who served as North Korea policy coordinator in the Clinton Administration and as lead negotiator for the Obama Administration in talks with Iran about its nuclear program.

Power opened by reading a humorous excerpt from her book describing how she first came to know her husband, Harvard Law School Professor Cass Sunstein, who stood in the back of the room as she spoke. Both Power and Sunstein were serving as unpaid advisors on the first presidential campaign of Senator Barack Obama ’91 when Sunstein inadvertently sent an undiplomatic email to the campaign’s entire senior staff. She “felt for Cass,” Power said, recalling that she’d recently made a similar mistake, sending an email about a blind date gone bad to a friend, only to discover that she had accidentally sent it to a listserv of thousands.

Soon, Power and Sunstein, both Boston Red Sox fans, were texting each other managerial advice during the games. “At first,” she recalled, “I didn’t attach special significance to the fact that I was taking an inordinate amount of time to craft these texts.” By July 2008, the couple had married and Sunstein began teaching at Harvard Law School in that fall.

Panelists Alford, Allison and Sherman found much to praise in Power’s latest book.

“This is a great book; great read; very well written; quite exciting. And I would say the takeaway is: law students can grow up to do good,” said Allison, eliciting laughter from the capacity crowd in Wasserstein Hall. But he found Power’s account of the Obama administration’s efforts to respond to the Syrian civil war “painful and unsatisfactory.”

“Is what the U.S. government has done in dealing with Syria good enough?” Allison asked. “I would say, as a harder-nosed realist, it’s good enough for Americans today. Half of the country is being displaced. Half a million people have been killed. President Obama announced famously ‘Assad must go.’ President Putin said ‘forget about it.’ … And have you heard a single peep about this from the Democratic candidates in the current campaign? I haven’t heard a single one. So, is this good enough?”

Citing Power’s 2002 book, “A Problem from Hell: America in the Age of Genocide,” in which she criticized America’s response to human rights atrocities abroad, Allison wondered whether her subsequent experience as a government official dealing with the Syria challenge has temper her previous views, or whether she would argue that Syria was “sufficiently different or more complicated.”

Responding later in the program, Power agreed with Allison critique. “I don’t think our response to Syria was good enough,” she said.

When he was dean of the Harvard Kennedy School, Allison had appointed Power as the founding executive director of the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy. Power credited Allison with suggesting the book’s title, which he said was inspired by “The Education of Henry Adams,” in which the grandson and great-grandson of presidents examined his life and his preparations for dealing with a rapidly changing world.

Sherman, who had served alongside Power in the Obama administration, said she was struck by Power’s description of how she effectively managed both her responsibilities as both a diplomat and a new mother, or as she described it, “life-work integration.” She also recalled meetings in the White House situation room, with Power struggling to make her points heard as she participated by video conference from her office in New York. President Obama, Sherman said, would always ultimately solicit Power’s view “because he knew she would push us all to think about the issue on the table in quite a different way.”

But Sherman’s most surprising revelation about Power was her initial reaction to her appointment as America’s Ambassador to the United Nations.

“Many of us doubted that she was the right person for the job,” Sherman said. “We thought she didn’t know enough about national security and foreign policy. She didn’t know enough about the United Nations. She always pushed the envelope, [which is] hard to do in a multilateral setting. [She] hadn’t had real legislative experience … and that’s what the U.N. is, it’s a legislative body in many ways.”

“But we were all wrong,” Sherman admitted, citing Power’s success convincing the U.N. Security Council to approve a resolution requiring Syria to destroy its arsenal of chemical weapons, as well as the council’s later unanimous vote in favor of the 2015 Iran nuclear deal.

Alford, who had served as her teacher and mentor during her time as a law student, contrasted Power’s memoir to those written by several of America’s former high-level diplomats, including Secretaries of State Dean Acheson [1918], Henry Kissinger and Henry Stimson [1888-1890]. Their volumes about their time representing the United States all “had an impersonal, Olympian quality which give their accomplishments … an air of inevitability.”

By contrast, he said, Power’s book “is remarkable … for its forthright rendering of Samantha’s and our vulnerability as human beings and what this means for who she sought to be and who she is … [It] is neither a self-congratulatory account of good triumphing over evil nor a self-chastising one about realism trumping idealism. Rather, it is a deeply probing exploration of the meshing of what we hope for with who we are, of idealism and ambition, and of individual and institution as forces in history.”

Power, Alford said, “speaks forcefully about the challenges and the opportunities that access to high levels of official power mean for one’s ideals and ideas.”

Near the end of the discussion, Power argued that making transformational change often requires many people to make change in smaller ways. Harvard Law students are an example of this phenomenon, she said, “through the work they do through their clinical programs to help people.”

Solving huge, global problems like the refugee crisis can seem impossible, she said, but it can be achieved by breaking the work into smaller pieces that individuals can tackle. “If everybody does their share, we can get to the transformational place,” she said. “But if we seek to bite it off all at once, that can be more challenging. So, I commend law students for the work they are already doing.”