U.S. capital markets are being dragged down by foreign competition. But we aren’t playing by the same rules.

On a snowy February evening in 2006, a small group of luminaries in the world of international finance gathered for dinner at the Harvard Club in New York City at the invitation of Professor Hal Scott, director of Harvard Law School’s Program on International Financial Systems.

His guests included R. Glenn Hubbard, dean of the Columbia Business School; John Thornton, chairman of the board of the Brookings Institution and former president of the Goldman Sachs Group; Donald L. Evans, CEO of the Financial Services Forum and former U.S. secretary of commerce; and Kenneth C. Griffin, managing director and CEO of Citadel Investment Group.

The conversation focused on a single topic: Had the United States lost its competitive edge among the world’s capital markets because of overly burdensome regulation and litigation?

Scott and his companions fretted over the fact that companies are increasingly going public in the London and Hong Kong exchanges rather than in the U.S. Possible reasons include the stringent reporting requirements of Section 404 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act—passed by Congress after corporate accounting scandals at companies such as Enron and WorldCom—and the burden of the U.S. litigation system.

The numbers were hard to ignore, they found. In 2005, only 5 percent of the money raised through global initial public offerings of stock was raised in the United States, compared to 50 percent in 2000. The U.S. share of equity capital raised in the world’s top 10 economies was an anemic 27.9 percent in 2006, down from 41 percent in 1995. And private equity firms—almost nonexistent in 1980— sponsored more than $200 billion of capital commitments in 2005 alone.

The immediate effects of a decline in U.S. capital markets are felt primarily on Wall Street. Once a market begins to lose its competitive position, the exodus of talented financial professionals begins, making the other markets even stronger. And, said Scott, “Once a market moves abroad, it is very difficult to get it back.” But Scott believes it’s not just Wall Street or Fortune 500 companies that will be affected. Without a vibrant domestic capital market, some U.S. companies would not have access to capital markets at all—particularly smaller companies, which are steady incubators of jobs and wealth for the U.S. economy.

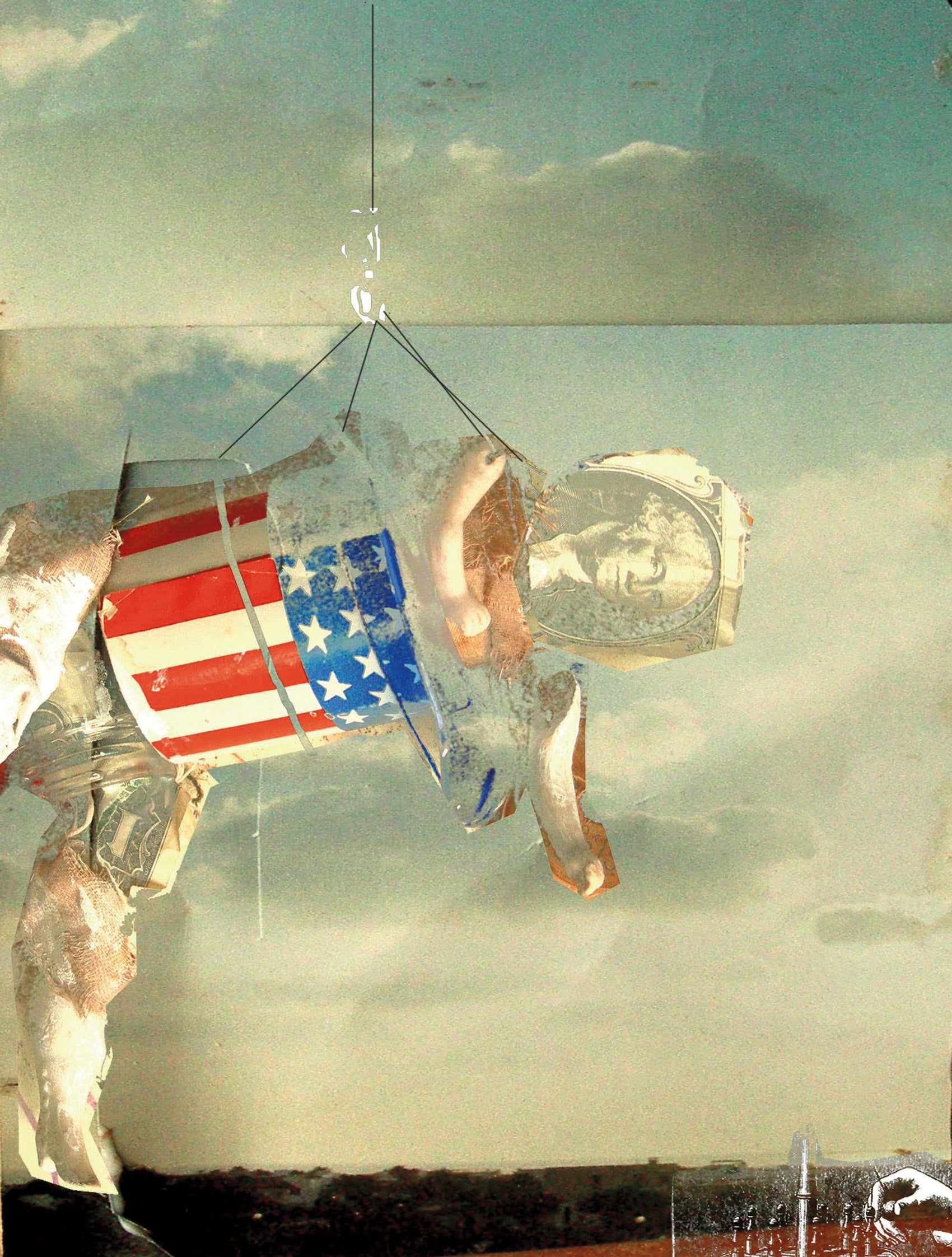

Credit: Asia Kepka Hal Scott: “We knew there were problems in keeping competitive and we were determined to do something about it.”

Scott and his guests believed they were witnessing a crucial moment in economic history. “We knew there were problems in keeping competitive in [this] area and we were determined to do something about it,” he said. They agreed to be the steering committee of a new group, which they called the Committee on Capital Markets Regulation.

The steering committee recruited members for what it hoped would be an influential, blue-ribbon team to examine the problem. “We never planned for this to be a purely academic exercise,” said Scott. “We felt it was not worth doing unless people believed it was going to have an impact.”

The panel they assembled included “the best and the brightest out there who had thought for years about these issues,” Scott said. CEOs Samuel DiPiazza Jr. of PricewaterhouseCoopers, Steve Odland of Office Depot, William Parrett of Deloitte and Jeffrey M. Peek of CIT Group were part of the group. Noted academics also joined the committee, including Peter Tufano of Harvard Business School and Luigi Zingales of the University of Chicago Graduate School of Business.

In September, when the committee formally announced that it would conduct a major study of how to improve the competitiveness of the U.S. public capital markets, the new treasury secretary, Henry M. Paulson Jr., announced his support of the project and his keen interest in the panel’s anticipated report and recommendations.

View More

In D.C., no rush to roll back “sox”

Sarbanes makes his exit, but his law may be here to stay

A year ago, it looked as if the Sarbanes-Oxley Act might face a serious overhaul after its two principal authors, Rep. Michael Oxley (R-Ohio) and Sen. Paul Sarbanes ’60 (D-Md.), retired from Congress at the end of 2006.

Read more.

Paulson’s support was important, but Scott and his colleagues knew they would need to capture the attention of other Washington policy-makers, too. To do that, timing would be key. New initiatives typically attract most attention after an election and before the new Congress returns. That meant an early November release of the report would be optimal, to have a chance at earning a spot on the calendars of legislators and regulators alike. And that gave the committee just two months to craft a plan for reform.

Working groups were divided into four areas of study: shareholder rights, the regulatory process, public and private enforcement, and Sarbanes-Oxley. HLS Professor Allen Ferrell ’95 was assigned primary responsibility for the shareholder rights section of the report. His colleague Professor Reinier Kraakman worked on the enforcement portion. And Robert Glauber, visiting professor of international financial systems at HLS, was tasked with writing the section on the regulatory process.

“It was a whirlwind,” said Scott. “And if I hadn’t been at Harvard Law School, this couldn’t have been done.” The project was aided by a team of 10 Harvard Law students. “They went into this 24/7,” he said, “researching, proofing, editing, going to meetings, taking notes. It was extraordinary. In terms of mobilizing people, there is nothing to compare with the platform of HLS, with its size, talent and depth.”

View More

Reforming financial reform

From a blue-ribbon panel, a slate of prescriptions for improving the health of U.S. capital markets

Some of the committee’s key recommendations…

Read more.

The committee released its 135-page report on Nov. 30, 2006. It made 32 recommendations in the four key areas it examined (see Reforming financial reform), with the twin goals of reducing overly burdensome regulation and litigation while enhancing shareholder rights. “As shareholders are able to take more control over companies in which they are stakeholders, regulation can be more targeted,” the authors explained.

Washington began to take notice immediately. Scott traveled to the Capitol in early December as Congress was rearranging itself after the Democrats gained control of both houses. He met with the new chairmen of the House and Senate financial services committees.

In the House, Barney Frank ’77, the ranking member of the Committee on Financial Services, expressed an interest in holding hearings this year on capital market competitiveness. On the Senate side, Christopher J. Dodd of Connecticut, the new chairman of the Banking Committee, said the report “makes a valuable contribution to our ongoing examination of international competitiveness, and I intend to review this report thoroughly in the coming days.” Dodd indicated an interest in holding hearings as well.

But it wasn’t welcomed in all quarters. Gov. Eliot Spitzer ’84 of New York, who rose to national prominence battling fraud on Wall Street when he was the state’s attorney general, warned that the recommendations would weaken the power of regulators and prosecutors. Scott replied: “Spitzer’s concern was about our proposed limitations on state regulation of capital markets through their enforcement powers—but we can’t let 50 states’ attorneys general regulate a national market of such importance.”

Scott is hopeful the report will attract the interest of the President’s Working Group on Financial Markets. Headed by Secretary Paulson, it counts among its members the chairmen of the Federal Reserve Board, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission. “We’ve sent a letter to the president asking him to issue an executive order asking the group to look at this problem and make a recommendation,” said Scott.

“The timing for the report is great,” he added, noting that some had feared that a Democrat-controlled Congress might not take an interest in its findings. “My read is the opposite of that. The Democrats can now claim credit for being part of the solution.”

Credit: Asia Kepka Oscar Hackett, Pengyu He and eight other HLS students “went into this 24/7,” said Professor Scott.

The students who were involved in the panel’s work said the experience was invaluable. “It was the highlight of my first semester,” said 1L Oscar Hackett. Before matriculating at HLS, Hackett worked for Deutsche Bank for three years. He appreciated the chance to rub elbows with professionals in the top echelons of finance and was impressed that Scott fielded calls from the White House during their meetings. “I came here to get involved in this sort of work, where I could potentially have an immediate impact on the U.S. economy,” Hackett said.

Pengyu He, a 3L from China, got involved in the project after an earlier research effort with Scott that examined why Chinese companies avoid U.S. capital markets. He said both projects “have been very illuminating in gaining a comparative view of markets. I’m very indebted to Professor Scott. I have learned a lot about his vision, and I like the combination of research and real-world issues.”

Scott isn’t idling as he waits for Washington’s attention. In December, he traveled to Europe to convey the report’s message at the behest of U.S. Ambassador to the European Union C. Boyden Gray. “If we reform our system and make it more like Europe’s, in the long term it will benefit everyone,” said Scott. “Then we can sit down and deal with the rules globally, instead of competing on the legal rules. To get to that, our rules have to be closer to theirs. If we’re successful in this effort, that will happen.”