For the first time in decades, HLS has changed the basic structure of its first-year experience, and students and faculty are singing the praises of The New 1L

When members of the Class of 2004 look back on their first year at Harvard Law School, maybe they’ll recall their first case or last final exam.

Or perhaps some will remember joining Professor David Westfall ’50 in singing “California Girls” to their visiting professor from UCLA at a karaoke night. And then there was the baby shower students organized for Assistant Professor Heather Gerken, complete with stuffed animals and a baby-shaped cake.

Welcome to the new 1L, where the seven smaller sections look like a cross between an intellectual salon, a social club, and a summer camp.

Equally important, though, is what’s going on inside the classroom. Class sizes slashed nearly in half. Written feedback guaranteed well before finals. More freedom to choose faculty advisers and spring electives.

“The real thrust of the 1L restructuring is to improve the students’ educational experience,” said Dean Robert Clark ’72. “It is a pedagogical shift that will help build up their analytical skills, which are really important to the practice of law.”

Taken together, the most striking changes in decades have transformed the gateway into Harvard Law. Student satisfaction has never been higher, but The Paper Chase‘s Professor Kingsfield would probably roll over in his grave.

It’s certainly not the same law school where deans once reminded entering students that one-third of them wouldn’t be around in a year. Now, a professor is more likely to serve them brownies in his or her living room.

So can Harvard Law still be as rigorous a school if it no longer terrifies students while educating them? And what happens when the high wall of formality separating professors from their prey finally tumbles for good?

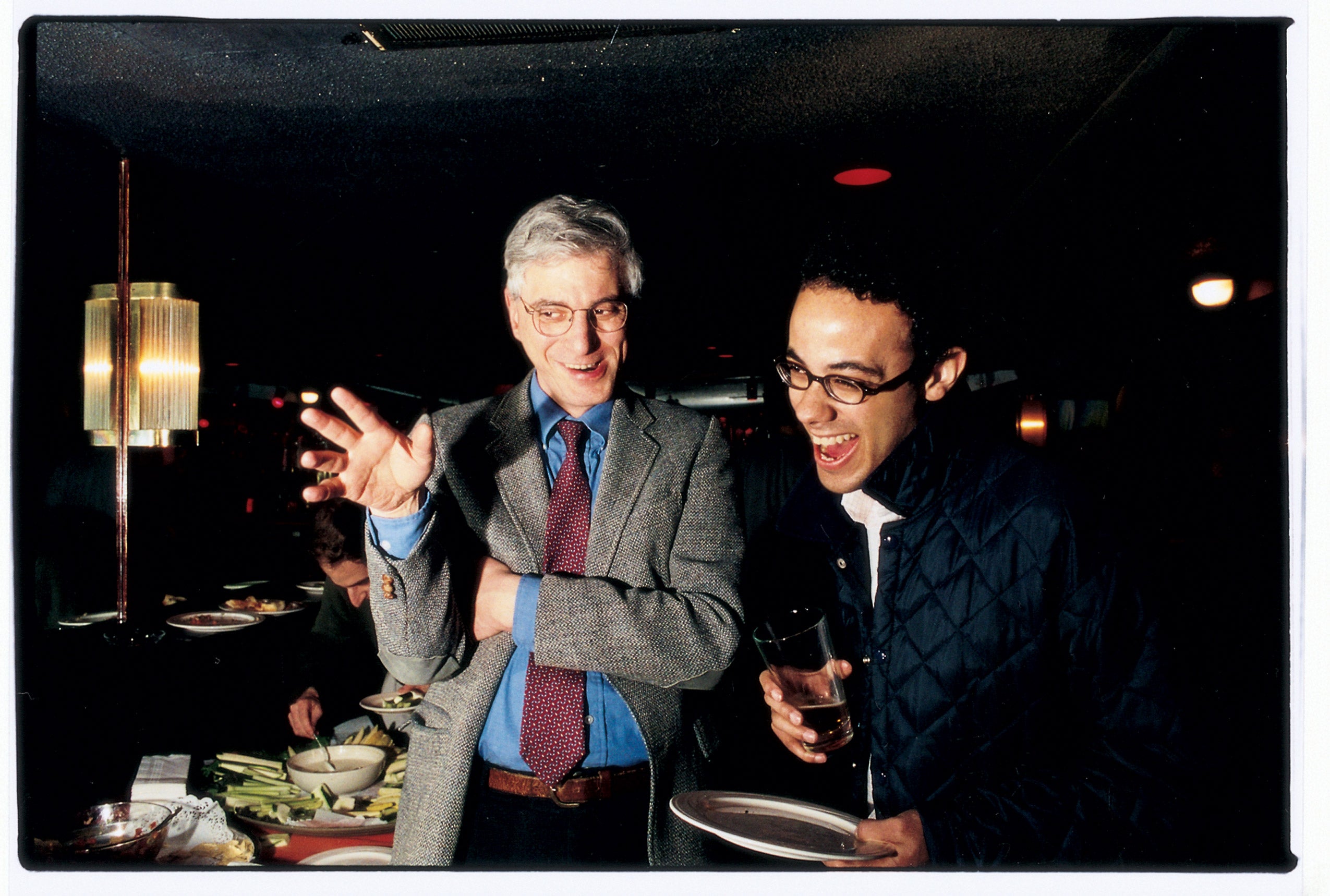

That’s what I wondered as I watched my former criminal law professor, Daniel Meltzer ’75, schmooze with his section while sipping a bourbon on the rocks in a basement bar.

Meltzer long ago earned a reputation for caring, advising what courses to take, and providing written feedback before it was required. Yet he still didn’t smile much before Christmas, and most contact generally ended at the edge of campus.

This year, Meltzer’s students visited his house twice–and that was even before he started teaching their class in February. It was just one piece of a schedule of activities designed to ease students into their first semester.

He calmed students’ first-day jitters with a mock class and organized a mixer where each of their professors introduced themselves. Midway through the semester, they talked about career aspirations with career counselors and what courses to pick in the spring.

They ate fajitas and played charades at a Christmas party in the Hark (Meltzer had the word spank). And when grades were mailed, he gathered students at a breakfast where he tried explaining why grades didn’t matter as much as they feared. “If you take 100 people who won the Nobel Prize in physics and rank them on a bell curve, someone would be ranked 100,” Meltzer told them. Few, though, seemed convinced.

When they entered the classroom for the first time, both Meltzer and his students felt more at ease together, they say. “After you get to know your professor is a person rather than just somebody who tells you information, it makes the interaction easier,” said 1L Alex Venegas.

Two months into the spring semester, they gathered on a school night at the Lizard Lounge, a basement bar next to the law school dimly lit red like a submarine.

In the morning, Meltzer will gently drill his students about search and seizure warrants. Tonight, they tell him about summer jobs and spring break plans. One recommends the margaritas. Another asks if his federal courts class really is the hardest course at the school. “People feel like they’re getting their four credits’ worth,” Meltzer said.

Many students say such interactions were downright awkward at first. “When we first got here, we had no idea what to talk about,” said Dave Dorfman. And students say they realize there’s a limit to the chumminess. “There’s still a distance,” said Anna Lumelsky. “They’re professors and we’re students–we speak to them as people who will be grading us.”

Others found it less difficult to mellow in the presence of their professors during karaoke nights and other social events. At a Boston piano bar one night, most of one section swayed to “We Are the World,” seeming not to notice that Professor Randall Kennedy sat chatting with a few students at the front table.

Professor Martha Minow said becoming buddies was never her goal. “What I can offer that’s distinctive is a window into the intellectual life of the profession,” she said.

Each section was scheduled a block of time every week when students had no other commitments. Minow invited a South African Supreme Court justice to talk about serving on the Rwandan war crime tribunal and had Professor Richard Fallon Jr. debate the merits of military tribunals with Professor Alan Dershowitz.

Four decades ago, when Professor Frank Michelman ’60 entered Harvard Law, even approaching a professor outside of class was simply unimaginable. “During my first year of law school, I did not set foot in a professor’s office–it would not have occurred to me to do so unless summoned,” he said.

In March, Michelman sat at the Boston piano bar with his students, raising a glass to John Mellencamp’s “Jack and Diane.” Much has changed in the intervening decades. Younger generations of students and their professors have brought different expectation¿ about how to relate. “The mores surrounding education have changed,” said Dean of the J.D. Program Todd Rakoff ’75. “Students are motivated by friendliness and less motivated by formality.”

Harvard Law didn’t necessarily fare well in that changed environment, ranking 154th out of 165 schools in student satisfaction in a 1994National Jurist magazine survey. Focus groups and surveys conducted by McKinsey & Co. as part of the school’s strategic planning process found similar dissatisfaction. One upperclassman reported feeling so alienated he wouldn’t notice if the school burned down.

The faculty too saw the need for change, voting unanimously in the fall of 2000 to carve up the first-year class into seven smaller “law colleges.” For years they’d debated what might be the ideal class size. They settled on 78, but no one was sure whether that would be the magic number capable of changing the dynamics inside the classroom.

But most professors say they were surprised to find what a significant difference reducing sections below 80 students made. “It has the effect of reducing the sense of formality,” Michelman said. “It feels easier.”

Learning everyone’s name takes days instead of weeks. More students speak up voluntarily. Students report getting called on more often and finding it more difficult to melt into the crowd.

With classes still conducted in rooms designed for the larger sections, there are more empty seats–yet fewer places to hide. Empty rows separate students from the back bench seats where the unprepared used to seek anonymity.

There has been some loss of intimacy since students no longer have a small section of 45. But many first-year students have found their class size fell even further in their electives. Instead of choosing from a small number of electives, each first-year student was able to enroll in any course this spring.

Jason Cowley, for example, found he was one of only five students in a human rights research seminar taught by Professor Mary Ann Glendon. “In terms of one-to-one interaction, it’s great,” he said.

In each first-year class, students were guaranteed feedback from each professor on a mandatory written assignment. No more waiting until finals for the first sign of progress. Most professors assigned sample test questions. Students also were given more freedom to select a faculty adviser who shared common interests instead of being assigned one randomly during orientation.

Additional direct feedback from professors came during the revamped First-Year Lawyering course, which replaced the previous incarnation, Legal Reasoning and Argument. First-Year Lawyering instructors provided written comments on memos and often one-on-one conferences.

FYL instructor Megan Dixon said she wound up talking to students about much more than just research memos. She listened to concerns about the pressures of law school and juggling outside lives. “I know each of my students extremely well,” said Dixon. “I’m sort of a face the students can come to and feel comfortable with.”

Of course, there are still kinks to be worked out in the new first-year experience. No one is quite sure at what point there are simply too many activities crammed into swamped students’ schedules.

Eventually, Minow hopes the sections will look more like undergraduate colleges–a place where students and faculty can share common experiences–even if they don’t yet have a space to call their own.

It’s unlikely each “law college” will soon have its own dorm, but professors hope each will one day get a common area where students can gather and hold events. For now, though, the only physical changes are larger mailboxes decorated with color photos of each section.

While the sections serve their most important function during the first semester, many students say they hope each section can maintain its identity through the remainder of law school. Some envision serving as mentors or guides to each new class as it advances. Minow said she plans to keep in touch with her current section while again serving as a section leader for next year’s entering class.

Quantifying the impact of all the changes isn’t easy. For one thing, it’s difficult to simply compare expectations of students before they entered with what they actually experienced.

After all, every entering class is pleasantly surprised when their first year isn’t as bad as they feared. Take Maya Alperowicz, who arrived at Harvard Law straight from college last fall with low expectations after reading Scott Turow’s (’78) One L and watching John Jay Osborn Jr.’s (’70) The Paper Chase. “I expected people to be really competitive, not to be friendly, and to be preoccupied with their own work,” she said.

Instead, she found her concerns dispelled. “I definitely feel there’s a sense of community in our section,” said Alperowicz. “It makes the law school a really human place.”

Interviews with dozens of other first-year students suggest a similar heightened satisfaction that wasn’t evident in the past. Even a year ago, students said they could go through their first year without getting to know a single professor or learning the names of everyone in their section.

Erin Hoffmann ’02, who served as president of the Board of Student Advisers, said she noticed the difference in the two sections she taught last fall. “They’re generally pretty lucky,” she said. “There’s more engagement in the academic experience.”

Even those who don’t like every element of their first-year experience still praise the school for making an effort. Most telling perhaps is a dramatic drop in the number of students seeking help from school health counselors for serious exam-related anxiety. And for the first time in memory, not a single first-year student reported they were unable to finish an exam on time, said Dean of Students Suzanne Richardson.

Minow said creating a greater sense of community among students and faculty proved particularly welcome after September 11. “It added a layer of social support which so often has not been the case at the school and, at a time of trauma, was very important,” she said.

As for the quality of education, professors bristle at the notion they’ve gone soft. In fact, Meltzer said more ease in the classroom actually makes it possible to push students harder.

“The question is did the rigor of Harvard Law School depend on the terror of Harvard Law School, and I don’t think it did,” Rakoff said.