As we grapple with disinformation driving the recent attack on the U.S. Capitol and hundreds of thousands of deaths from a pandemic whose nature and mitigation is subject to heated dispute, social media companies are weighing how to respond to both the political and public health disinformation, or intentionally false information, that they can spread.

These decisions haven’t taken place in a vacuum, says Jonathan Zittrain ’95, Harvard’s George Bemis Professor of International Law and Professor of Computer Science. Rather, he says, they’re part of a years-long trend from viewing digital governance first through a “Rights” framework, then through a “Public Health” framework, and, with them irreconcilable, most immediately through a “Legitimacy” framework.

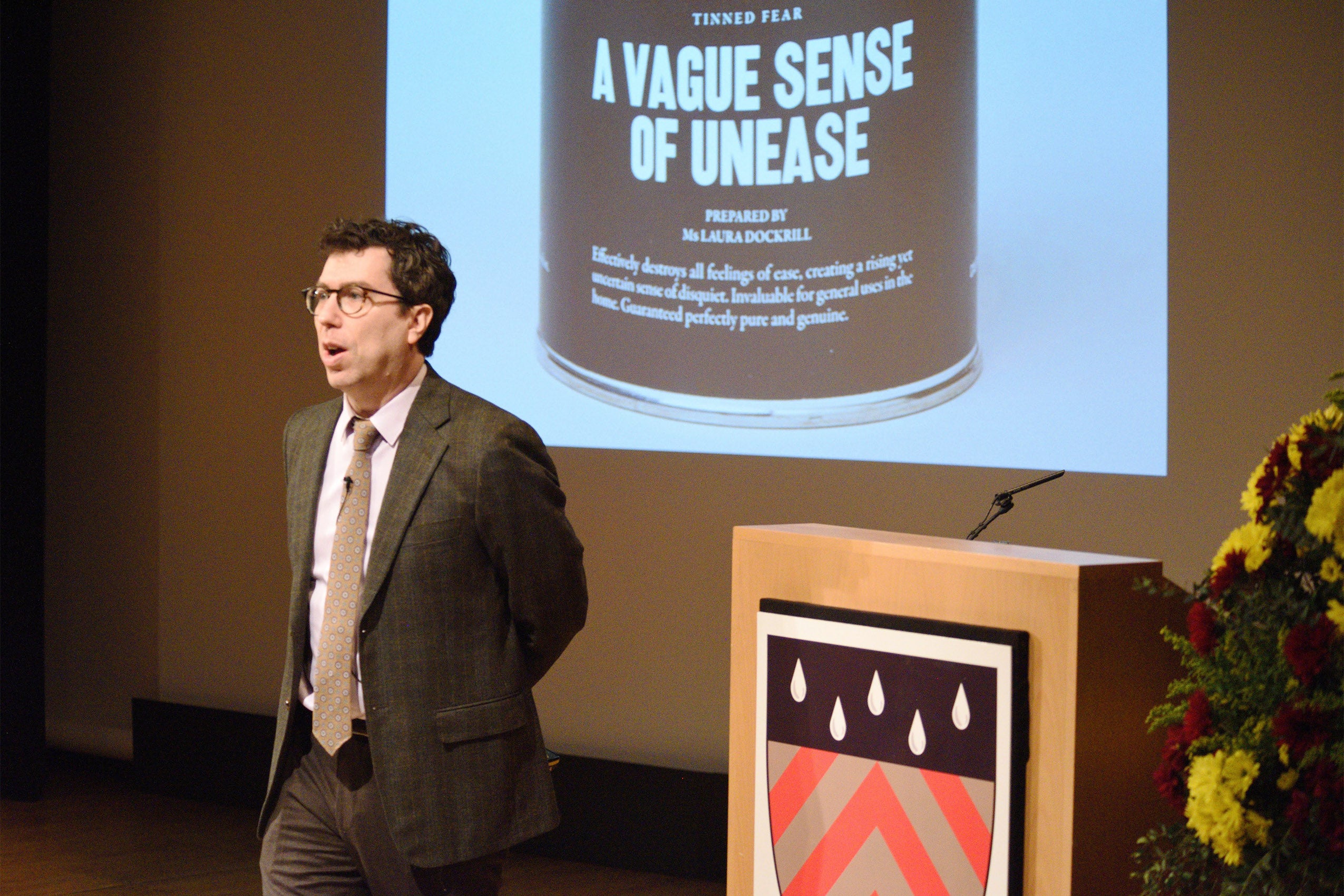

Zittrain, co-founder of the Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society, delivered his remarks as part of the first of two editions of the 2020 Tanner Lecture on Human Values at Clare Hall, Cambridge, a prestigious lecture series that advances and reflects upon how scholarly and scientific learning relates to human values.

According to Zittrain, former President Donald Trump’s deplatforming from Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube, among others, is one of the most notable recent content moderation policy decisions — one which Facebook just referred for binding assessment by its new external content Oversight Board.

In contrast to the two preceding eras and philosophies of the digital governance, owners and users alike have recently begun working to imbue platforms with legitimacy by “looking for ways of facilitating agreements among the people affected across jurisdictional boundaries. To formalize governance processes them in some way, effectively negotiating them, writing them down, and carrying them out in public view,” Zittrain said.

The “Rights era” is based on ideals of internet freedom from government intervention and rooted heavily in 1990s literature, such as John Perry Barlow’s essay, “A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace.” But by 2010, Zittrain said, the Rights era evolved into a “Public Health era” demarcated by concerns about the quality of content promoted by platforms like Google and voice assistants and the increasingly targeted advertising ecosystem driving social media sites.

The Public Health era, Zittrain explained, “focuses on the ways in which technology is allowing new forms of harm to come about, but may contain within it the seeds of amelioration, if only we are bold enough to compel or sway those intermediaries, those platforms that are empowering us also to impose limits and control in the name of public health.” The underlying question of this time, Zittrain posed, is “When does can imply ought?”

“When is it that when you can do something, you’re morally obligated to – on pain of responsibility, should harms arise from your inaction?” he continued. “Technology companies are now capable of intervening in the harmful dynamics they themselves enable at an unprecedented level of granularity – and because they’re so often walled gardens, nobody can do so for them. So when they abdicate, are they failing morally in a manner that might demand, among other things, regulatory intervention?”

Today, platforms are under increasing pressure from both internal and external forces calling for accountability and reducing the adverse effects of their technology. This pressure provided the foundation for what Zittrain calls the “Process era.”

Zittrain, who leads the Berkman Klein Center’s Assembly: Disinformation program, outlined suggestions for navigating the current era, some of which are already at play today. For example, he discussed “binding shifts of control outside of the firm,” illustrated recently by the nascent Facebook Oversight Board. He also suggested that companies preserve data for researchers to study, and that they use this era of change to experiment with new modes of governance. “Don’t try to develop one perfect thing that then won’t work and say, ‘Well, we tried process. But it didn’t work.’ Try lots of processes in this time. Taking advantage of the uncertainties that are here.”

Actions such as experimenting with flags about misinformation on social media posts and limiting interactions with harmful posts are two examples of such ideas, iterated on over time and applied in various contexts.

Zittrain also suggested expanding the “learned professions,” such as divinity, law and medicine, “each with a respective form of power that they come into through their training, for which they then have duties to their parishioners, their clients, their patients that go beyond the commercial,” to encompass employees at these digital intermediaries. Employees working on new technologies like autonomous vehicles, social media platforms, and devices should not be driven by their companies’ bottom line, but instead by a moral and ethical code, similar to doctors and lawyers, Zittrain said.

“I think it’s probably time to think about more learned professions. So that the data scientists, the engineers, the people in the engineering areas of a Facebook, of a Google – even if it’s a two-person startup, because sometimes those things get very big – have a sense of compass independent of just ‘what does my employer think.’”

Considering how to reconcile this internet history with current events, Zittrain referred back to Barlow’s 1996 aspiration at the end of his lecture: “‘May our civilization of the mind be more humane and fair than the world your governments have made before.’”

“This is a charge to us to figure out what that civilization would look like,” he said. “How can we draw in to that project our children, our students, ourselves, and ultimately the authorities? These are not contained problems. It’s a complex system that will affect the kind of government we’ll get.”

Zittrain joins a long line of esteemed scholars invited to deliver Tanner Lectures, including Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, philosopher Jürgen Habermas, and author Toni Morrison. “The Tanner Lectures were established by the American scholar, industrialist and philanthropist, Obert Clark Tanner in 1978. The purpose of the Tanner lectures is to advance and reflect upon the scholarly and scientific learning related to human values,” their website says.