COVID-19 presents a unique threat to people in prisons and jails, agreed panelists at “Incarcerated Populations and COVID-19: Public Health, Ethical, and Legal Concerns,” a webinar hosted by Harvard Law School’s Petrie-Flom Center for Health Law Policy, Biotechnology, and Bioethics on May 20th.

The panel, organized by Executive Director Carmel Shachar J.D./M.P.H. ’10 and visiting scholar Stephen Wood, was one of a series of livestreamed COVID-19-related events hosted by the Petrie-Flom Center. It featured interdisciplinary perspectives from law, public health, and bioethics.

“We know that congregate settings are one of the areas where we need to be particularly diligent and aware against the spread of COVID-19,” said Jessie Rossman ’07, staff attorney, ACLU Massachusetts.

“The numbers are really striking,” Rossman continued. “When there is an outbreak at jails and prisons, it can spread extraordinarily rapidly.”

For example, Rossman said, nearly 70% of the population at Federal Correctional Institution, Lompoc in California tested positive for COVID-19.

Rossman is heading up litigation in Massachusetts to protect prisoners during the pandemic, with the goals of reducing populations inside these facilities and implementing widespread testing.

Currently, lockdowns are the main strategy used by Massachusetts corrections facilities to stop the spread of COVID-19, said Joel Thompson, managing attorney at the Prison Legal Assistance Project at Harvard Law School.

The result, Thompson explained, is effectively solitary confinement.

“Our clients are reporting getting out of their cell maybe a half an hour a day,” he said, “Long enough to maybe take a shower or get some limited form of recreation or walking around before going back in their cell.”

In many cases, outdoor time, programs, classes, and visits have been cancelled, Thompson said. Prisoners have even more limited access to phone and email, and mail has been slower than usual. Because staffing is limited, prisoners’ diets have become more limited, too. And access to medical and mental health care is reduced.

Thompson said he has heard reports of prisoners decompensating in the lockdown without access to medical and mental health care, and other health concerns, such as diabetes and seizure disorders, are worsening without regular access to care.

Thompson adds that the pandemic has exacerbated longstanding, known problems with the prison system in the U.S.

“There’s a reckoning here, and it involves responding adequately to the pandemic, but it also involves confronting things that we know have existed,” Thompson said, such as the lack of agency individuals have while incarcerated, the lack of transparency within and outside of prisons, and the lack of post-release support for formerly incarcerated individuals.

And the issue extends beyond the criminal justice system, added Karthik Sivashanker, assistant professor of psychiatry at Boston University’s School of Medicine and staff consultation-liaison psychiatrist at VA Boston Healthcare.

“It’s not just about criminal justice,” Sivashanker said. “Race, class, and other factors determine how and when we die (and if we will die in jail).”

Sivashanker explained that structural inequities, such as those related to race and class, have profound, lasting ripple effects.

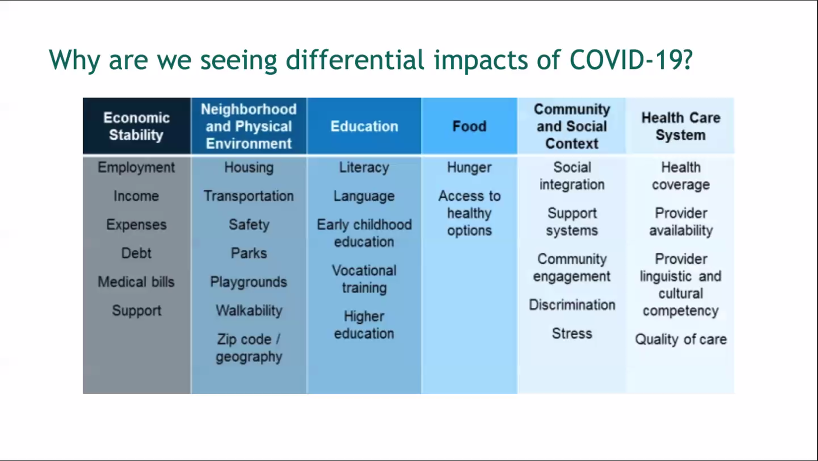

“The problem has been that we’re very fragmented, so, in health care we’ll talk about health disparities, in juvenile justice, we’ll talk about disproportionate minority contact. In education it’s the achievement gap. But once again, at the end of the day, we’re all talking about the same thing,” he said. “It’s the history of structural inequities—with economics, with neighborhood and physical environment, with education, with food, with our healthcare system.”

Sivashanker added: “Until we start talking about it and approaching it as the same thing—i.e., structural racism— and then coming together to work on it, we’re not going to make a ton of progress.”

COVID-19, he said, has been “both a magnifying glass and also a mirror. A magnifying glass in terms of magnifying the problems that we already have and have known we’ve had, and a mirror in terms of being able to reflect on the things that have been going well and that have not gone well. When we start to think about the future, when this is all over, when COVID-19 has died away and the next crisis is on the horizon, what should change? The answer really needs to be everything. Everything needs to change, from our laws, to our policies, to our practices … we’re going to need some really fundamental changes to get to the place where we need to be.”