It started, like the filing of every lawsuit, with the question of proper forum. Or, as Chinyere Amanze ’22 succinctly put it in her oral argument, “This case is about the awesome power of personal jurisdiction.”

On November 16, the Harvard Law School Ames Moot Court Competition — one of the most prestigious contests of appellate brief writing and advocacy in the nation — returned to the Ames Courtroom, as two teams of third-year students squared off on the subject of personal jurisdiction before a renowned group of arbiters including Elena Kagan ’86, associate justice of the United States Supreme Court; Kimberly S. Budd ’91, chief justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court; and Consuelo Maria Callahan, United States Circuit Judge for the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals.

The Ames Moot Court Competition begins during students’ second year, with qualifying and semi-final rounds, both of which were held online last year due to the pandemic. For Tuesday’s teams, the judges, and audience members, masks did not dim the thrill of being back in person at historic Austin Hall to witness this year’s Ames final round — a tradition that has spanned more than a century.

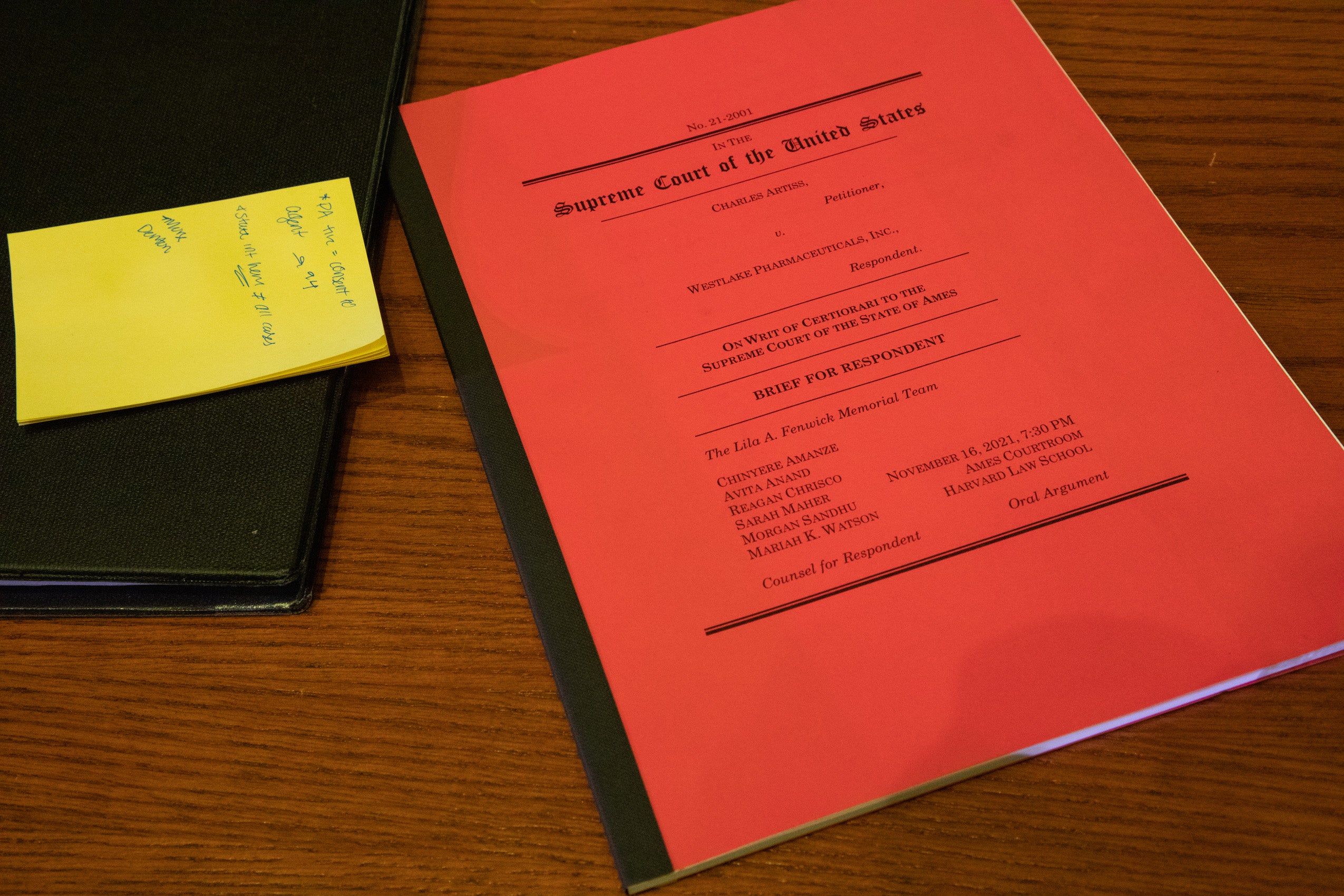

The event began with a warm welcome from Stacy Livingston ’22 of the school’s Board of Student Advisers, who introduced the finalists: the Carrie E. Buck Memorial Team, advocating for the petitioner, and the Lila A. Fenwick Memorial Team, representing the respondent.

After 70 minutes of lively arguments, pointed questioning from the judges followed by rapid-fire responses from the oralists, and a few laughs, the prestigious panel honored Morgan Sandhu ’22 as best oralist, with the Carrie E. Buck Team taking the prizes for best overall team and best brief.

“I was incredibly honored to be named best oralist,” said Sandhu. “I was truly impressed by everyone and I know how hard we all worked. It was particularly meaningful to hear the judges praise our different styles, as we all argue very differently. While it is obviously the oralists answering questions on the day of argument, it would have been impossible to be prepared without the constant pushing and refining that happened through team moots, so I think that as much as I’m excited for and proud of myself, being named best oralist really is a recognition of all that our team did together.”

“This has been the absolute highlight of my time at Harvard Law School. It was an incredible experience that I will treasure forever,” said Jason Altabet ’22 of the Carrie E. Buck Team.

Is Ames the right place to sue?

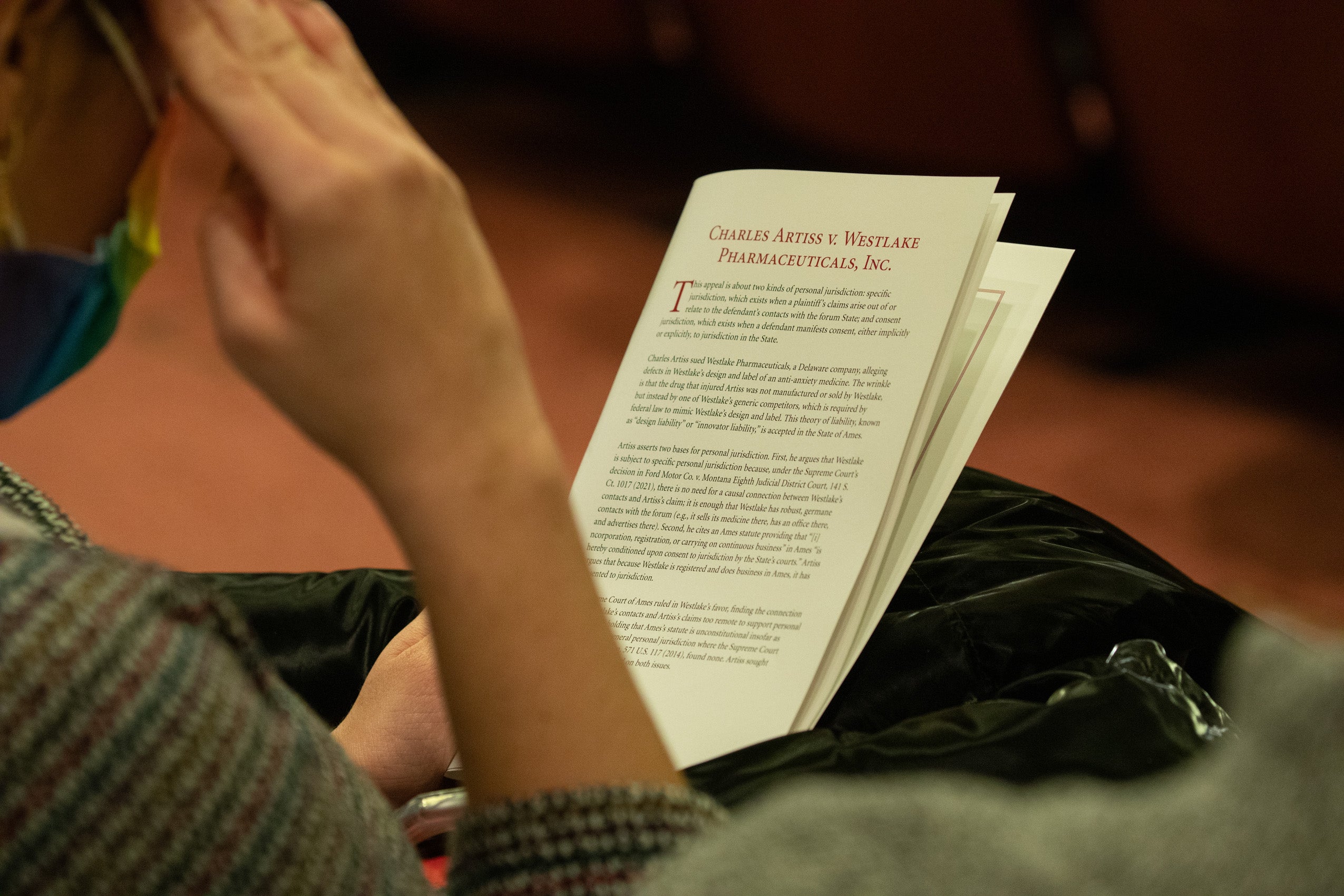

This year’s hypothetical case, which was written by Tejinder Singh ’08, asked the teams to address one of the foremost hurdles in a lawsuit: personal jurisdiction.

Due process requires that a court have jurisdiction over the party being sued. Such restrictions prevent plaintiffs from “shopping” for a forum that is more favorable to their claim, while providing more predictability as to where defendants can expect to appear in court. Two types of personal jurisdiction over corporations have emerged: general, which allows suits of all kinds where a defendant is “at home,” including where it is incorporated or headquartered; and specific, which permits a narrower slice of claims that “arise out of or relate to the defendant’s contacts with the forum.”

In Singh’s hypothetical case, the respondent, Westlake, is a pharmaceutical company incorporated in Delaware with headquarters in New Jersey, which sells products nationwide — including in Ames, where it has a small office and is required to register with the state to do business there. Westlake has repeatedly renewed this registration, even after Ames passed a law granting the state general jurisdiction over companies that do so.

Several years ago, Westlake created a new drug, DZ, to treat anxiety. Eventually, Westlake’s patent expired, allowing third parties to make and sell generic versions of the drug, which are, by law, required to copy Westlake’s formula and warning label. Charles Artiss, the petitioner and a resident of the state of Ames, was injured in a car accident and prescribed DZ. The pharmacy dispensed a generic version of the drug, one not manufactured by Westlake. Soon after taking the drug, Artiss suffered permanent injuries from a side effect that was not included on its warning label.

Artiss sued Westlake in Ames under Ames’s theory of “innovator liability,” which makes a name brand manufacturer liable for injuries caused by a generic version of the drug. But before the case could be heard on the merits, Westlake objected, claiming that Ames lacked personal jurisdiction over the company. On appeal, the Supreme Court of Ames agreed with Westlake and dismissed the case.

The Arguments

Appearing for Artiss, the Carrie E. Buck Memorial Team included John Acton ’22, Matt J. Bendisz ’22, Ryan Dunbar ’22, and Maria Huryn ’22, with Jason Altabet ’22 and Fenella McLuskie ’22 serving as oralists. The group said it had named itself in honor of Buck, a woman forcibly sterilized in Virginia after the Supreme Court upheld the legitimacy of the state’s eugenics law in 1927.

McLuskie began by asserting that Ames had specific jurisdiction over Westlake for Artiss’ injury. In the petitioner’s view, Westlake’s extensive contacts in Ames meant it had “availed itself of the [the state’s] market.” And because Westlake was solely responsible for the incomplete labeling on both its DZ drug and the generic version Artiss took, it should be subject to suit in Ames, she said.

“But was the label made in Ames?” asked Judge Callahan.

No, replied McLuskie, adding that the U.S. Supreme Court’s recent decision in Ford Motor Co. v. Montana Eighth Judicial Dist. foreclosed this argument. Westlake had marketed DZ in Ames, she said.

But it wasn’t Westlake’s drug, pressed Chief Justice Budd. “If it wasn’t Westlake who provided the drug, why should they have to answer for the injury?”

Westlake was responsible for the label, regardless, responded McLuskie.

Next, Altabet argued that Westlake could be sued in Ames because, under Ames Section 5101, the company had consented to general jurisdiction. “Six years ago, Westlake consented to a simple agreement that it would accept the jurisdiction of Ames’s courts in exchange for the benefits of being a registered foreign business in the state,” he said. “Twice since that initial agreement, Westlake has renewed its consent, and it has never attempted to withdraw.”

“How is this consent?” Justice Kagan broke in, adding that in order to do business in Ames, Westlake had to register. “It’s like a gun to your head.”

“I’m having trouble with foreseeability. Where is the line?” asked Budd, furthering Kagan’s argument.

Altabet countered that Westlake could have simply decided not to sell its products in Ames, but because the company concluded that the benefits outweighed the negatives, it chose to register. The consent itself was enough to satisfy due process, he argued.

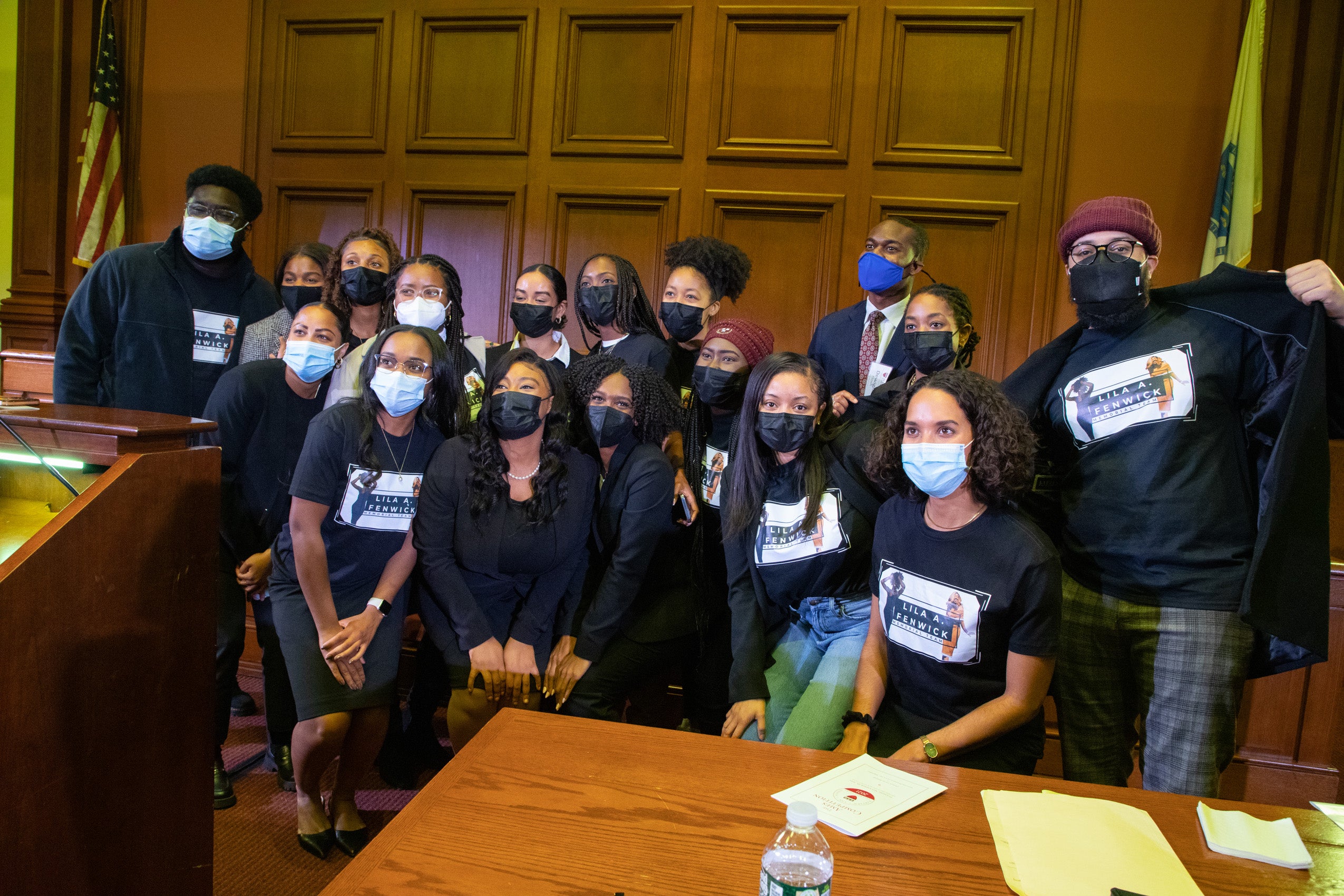

Up next, the respondent, Westlake, was represented by Avita Anand ’22, Reagan Chrisco ’22, Sarah Maher ’22, and Mariah K. Watson ’22, with Chinyere Amanze ’22 and Morgan Sandhu ’22 as oralists. Competing as the Lila A. Fenwick Memorial Team, the group said it had chosen its name to celebrate Fenwick, Harvard Law’s first Black woman graduate and a human rights advocate who passed away from COVID-19 in 2020.

Amanze began by arguing that specific jurisdiction was inappropriate over Westlake. “The essential tenet of specific jurisdiction is a connection between the plaintiff’s claims and the defendant’s actions in the forum state. There is no such connection here.” Ford is distinguishable, she said, because “the injurious product was not produced by Westlake.”

Moreover, “none of the labeling activities happened in Ames,” she said, adding that the petitioner could not use the “innovator liability” theory to sidestep jurisdictional requirements. The Supreme Court of the United States, said Amanze, has not thrown out the requirement that there be a “strong nexus between claim and action.”

“But Ford seems to leave open the option of potential. Someone named Justice Kagan wrote that,” quipped Callahan.

Next, Sandhu battled the petitioner’s claim of general jurisdiction, asserting that Ames Section 5101 was an unconstitutional violation of Westlake’s right to due process.

“As this court has made clear not once, not twice, but three times, a corporation may be subjected to general jurisdiction only where essentially ‘at home,’” she said, adding that the Ames statute was not truly “voluntary” in a modern economy.

Rather, said Sandhu, consent had been extracted from Westlake. Voluntariness, she said, requires choice.

“But can a party never give open-ended consent?” asked Callahan. “What if the state offered it a billion dollars in exchange for accepting general jurisdiction, would that be unenforceable?”

Ultimately, Sandhu said, the Court should view jurisdiction over Westlake as a violation of fairness, and an erosion of the line between specific and general jurisdiction.

The Court of Ames Rules

After both teams rested, the jurists deliberated, returning after making what Kagan said was a tough decision. “It did not seem obvious at all who should go home with the prizes,” she said.

“I just want to say how impressed I am with all of you,” added Budd. “It takes a lot of work, and you did beautifully.”

Callahan said she could have more easily decided the case than pick between the teams and oralists. “Your briefs were page-burners; the introductions were so much fun. You were all just amazing,” she said.

Finally, Kagan announced the winners: Sandhu was awarded best oralist, with the Carrie E. Buck Team taking best overall team and best brief. Kagan also reminded the participants that, regardless of their awards, they could all take pride in making it to the final round of Ames. “People have gone on to great things from where you’re sitting right now,” she said.

The teams, for their part, were honored – and exhausted.

“I’m so proud of our team and it’s surreal that it’s all over,” said McLuskie, of the Carrie E. Buck Team.